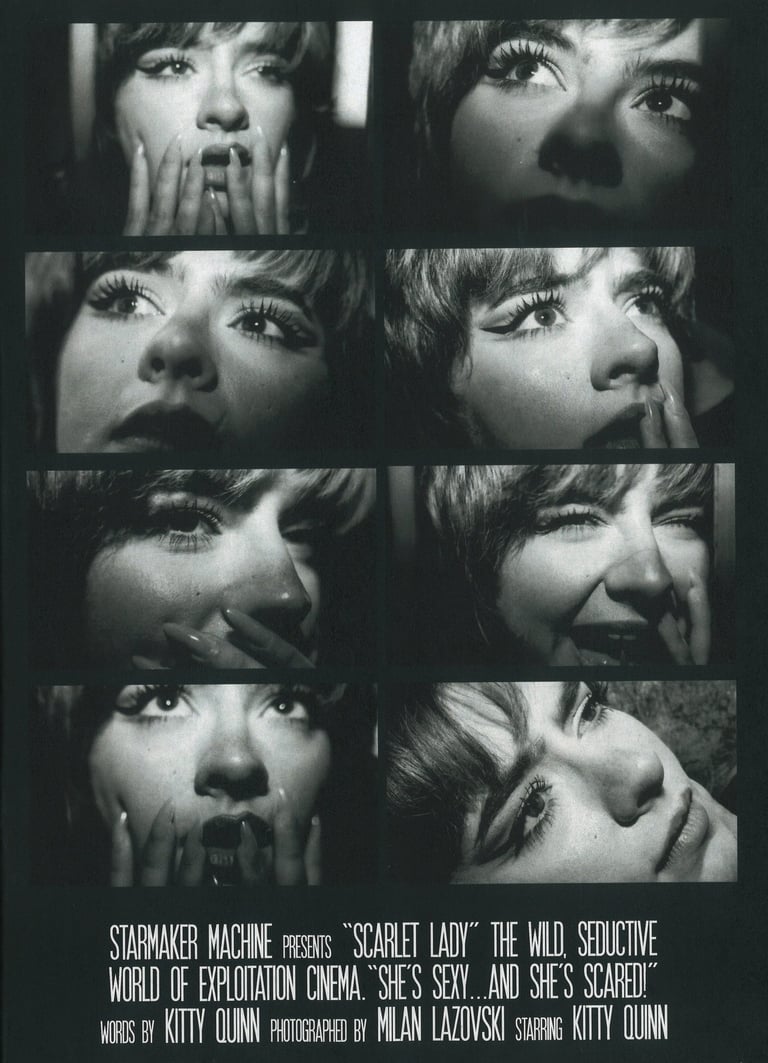

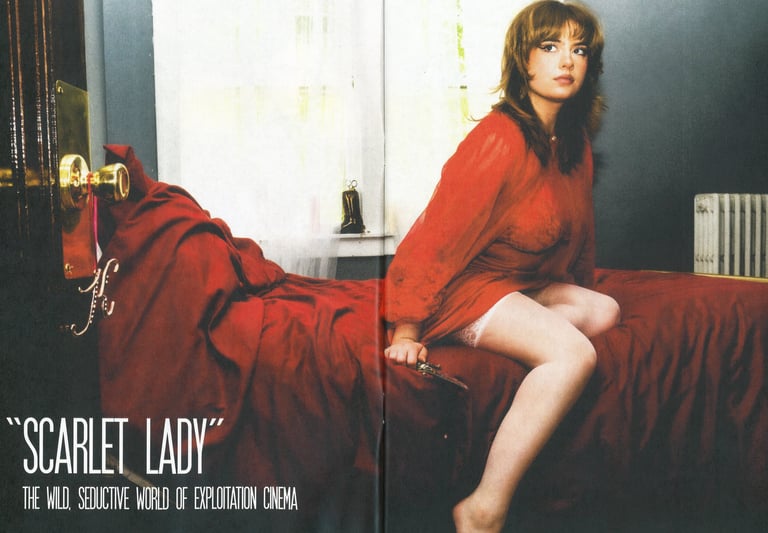

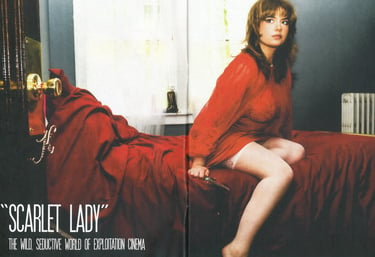

“SCARLET LADY”... THE WILD, SEDUCTIVE WORLD OF EXPLOITATION CINEMA

Written by Kitty Quinn, Photographed by Milan Lazovski, Model: Kitty Quinn | Apart of Issue #1 "STILL"

FILM

10/26/2024

Amidst the abandoned corridors of Hollywood’s golden age, where glamor and refined tales of romance thrived, another breed of cinema was born—peeking up at its glowing counterpart through worn floorboards. It was downright ugly, and shameless too. Exploitation films crept their way into the zeitgeist of the times with their provocative themes, cheap thrills, and thrived on the coattails of breaking the rules; leaving the harsh confinesof respectability in the dust. Caution was left to the wind and it revealed itself by exploring themes of sex, violence, and shock in order to lure unsuspecting victims towards the seedy underbelly of cinema.

Contrary to belief, exploitation films didn’t quite get their start in a Hollywood studio, but instead began brewing within the smoky confines of grindhouse theaters, where audiences were sucked in with tantalizing taglines and the promise to reveal all that is forbidden. The genre’s roots can be traced back to as early as the 1930s, when society’s rigid moral traditions threatened to boil over with curiosity of taboo subjects slowly creeping up. America entered the exploitation genre cautiously, while Europe stayed ahead of the curve. Czech film Ecstasy (1933) exemplified this, featuring a fully nude Hedy Lamarr. In Hollywood, films like Reefer Madness (1936) used fear-mongering to explore themes like drug addiction, premarital sex, and juvenile delinquency—but rather than teaching morality, these films sensationalized vice in a way that had never been seen before. During this time, the Hays Code was in full effect in an attempt to keep Hollywood wholesome, yet a few clever filmmakers were able to sidestep censors and lean into scandal by showcasing “bad behavior” like prostitution, drug use, sex, etc. being punished at the end of their films.

By the time the 1950s rolled around, a new kind of exploitation film began to emerge—capitalizing on cultural shifts and the sexual awakening sweeping America post World War II. Russ Meyer, a combat photographer during the war, recognized this shift and was thus dubbed as “The King of Nudies”. With his feature film The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959), Meyer solidified his role within the genre with a cheeky wink and grin—his films featuring satire, well-endowed women, and a playful yet provocative air without delving too deeply into the explicit. Another film of his, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965), became an instant cult classic that showcased sex, violence, and strong female leads that proved to be hypersexual beings with power over men— proving Meyer’s ability to push boundaries and deliver a thrilling ride for audiences.

While Meyer thrived with his tongue-in-cheek sexuality, other filmmakers made a point to go straight for the jugular in a literal sense. The 1960s and 1970s saw a rise in subgenres, each more gutsy than the last. Blaxploitation films brought the exploitation ethos a step further, with films like Super Fly (1972) and Shaft (1971)focusing on black protagonists who defied the subservient norm for people of color in traditional Hollywood. These films not only showcased action, but also stood as cultural statements. Issues like police brutality, systemic racism, and black empowerment were depicted in a style that

was unapologetic and raw for the very first time—solidifying actors like Pam Grier and Richard Roundtree as icons of the genre.

Meanwhile, in grindhouses, Herschell Gordon Lewis was paving a new way for horror. With his film, Blood Feast (1963), Lewis introduced the “splatter” film, where blood and carnage took center stage. With what it lacked in taste, it surely made up for in total shock value. With scenes of grisly murder and grotesque violence becoming his signature, crowning him the “Godfather of Gore” title, Lewis paved the way for the intense slashers that would take precedence over the horror genre in the 1980s.

As previously stated, the exploitation genre was not unique to America; it was also gaining traction overseas and in a more progressive way, most notably in Italy. Directors like Dario Argento and Mario Bava lead the masses with the giallo genre, beautifully gift wrapping it in a wide array of colors and unabashed violence, perfectly melding horror and art.

Furthermore, the Italians took it a step further with films like Cannibal Holocaust (1980) directed by Ruggero Deodato, which became notorious for its grisly depictions of cannibalism, blurring the lines between fiction and reality with its documentary style. This choice is what later resulted in the banning of the film across several countries—proving the extent of exploitation’s willingness to cross every boundary in the name of pure shock.

By the time the 1980s rolled around, ironically enough, traditional exploitation films became fewer and further between as the classic elements of the genre had started becoming mainstream. Hollywood had finally caught on to its ugly younger sibling, horror films notably adapting to many tropes that exploitation had pioneered over time. However, exploitation never truly saw its demise, its essence seamlessly woven into the fabric of modern cinema with filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino building their careers in homage to grindhouse and exploitation.

Though its prime may have passed, exploitation remains a crucial aspect of film history. Born from rebellion, it pushed boundaries with its raw depictions of sex, violence, and exploration of the taboo. The fearless approach of exploitation paved the way for modern filmmakers to blur the lines between art and controversy. In the current climate, where taboo has become mainstream and a shock is a storytelling tool in every area of the world, it’s clear that exploitation cinema left a lasting, lurid mark on the industry.