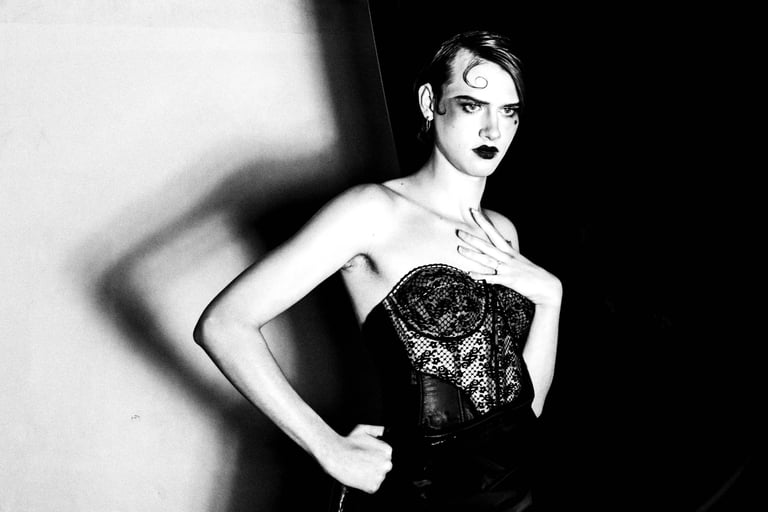

The Dances of Horror, Vice & Ecstacy in the Weimar Republic

By Kitty Quinn, Photographed by Milan Lazovski, Makeup by Kitty Quinn, Models: Andy Gucciardo & Izzy Parker

9/13/2023

Established just days prior to the end of WWI on November 9th, 1918, The Weimar Republic was the new democratic government created following the crumbling of the Second Reich. Although stricken with issues like hyperinflation in its early years, by 1924 stability was restored in the nation and they were able to enjoy a short-lived golden period where art and cinema flourished and social policies became more forward-thinking. Coined the home of the first gay rights movement, the Weimar Republic became legendary for its views on sexual liberation— Berlin, especially, providing some semblance of freedom for outsiders of society specifically within the queer community.

Germans culturally categorized these social groups under a single umbrella, rather than intersectional subjects. This led to fighting for reform in regards to female sex workers and trans or gender nonconformists becoming especially hard, as they were lumped in with homosexuality, thus being deemed as “abnormal sexual behavior”. Despite their newfound autonomy, due to opposition, queer people of any class were forced to the corners of lowbrow society within the larger cities— the motto of ‘out of sight, out of mind’ keeping heterosexual society at ease for a period. However, with literacy rates on the rise and better access to travel, gay and trans communities began to spread outside of the cities and across the republic resulting in high anxiety from conservatives. Still trembling with fears that traditional values would become entirely eradicated, conservative groups fought for staunch censorship as more decadent films and art became widespread. It didn’t help that many queer films were created by Jewish people, resulting in anti-semitism and homophobia joining forces. Many conservative groups argued that these pro-queer movements and media were a way for Jewish people to destroy the “pure” and “wholesome” German traditions— accusing gays and lesbians of being traitors of the nation.

Alongside this ever-changing political atmosphere, Germany saw several developments within art and media. With the Weimar Republic still being under the ban on all foreign films from the start of WWI, there became a dramatic increase in German films yearly; resulting in German expressionism becoming one of the most influential movements in cinematic history. Expressionism is characterized by its visual distortion and expressive performances, rejecting cinematic realism to reflect the woes of Germany’s society during the 1920’s. Films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis are some of the most famous examples of German expressionism and are often cited as some of the most sparkling instances of how set design can be used to create a world that fits perfectly through the film’s emotional lens. Furthermore, this movement also gifted the world with some of the first portrayals of queer love and desire through films like Mädchen in Uniform (1931), showing tenderness in love shared between women, and Michael (1924), a study of shifting power between muse and artists with a homoerotic main pairing— amongst many others. The survival of these films is a testament to the resiliency of queer communities during this time and paved the way for future queer narratives on screen.

This movement gave way to a number of queer icons that are still heavily referenced to this day. Though there are too many to mention, landmarks like Marlene Dietrich continue to be known within the cultural zeitgeist, whilst her colleagues like Anita Berber and Sebastian Droste have faded towards obscurity. Despite now only being eccentric footnotes of a front much larger than themselves, the pair’s success mostly came through how they influenced those with greater outreach and talent. Their cabaret act wasn't much different from others at the time, but their salacious, naked and kinky stage performances evoked shock even in those who had seen it all. The pair lived fast lives that dripped with glutton, their legacy only expanding due to art created following their deaths. Examples of this are shown through the likes of painter Otto Dix, who immortalized Berber in 1925 with his painting, “The Dancer Anita Berber”, and San Franciscan Photographer Francis Bruguiere, who featured Droste in his renowned expressionistic photographs titled, “The Way”. It took the visions of others to elevate the decadent duo’s status to a level they had craved in life— serving as another reminder of the strength and lasting power of communities that have always been there throughout history, even in the shadows of oppression.

While the Weimar Republic was short-lived, and the queer community faced subsequent persecution— t Goldene Zwanziger (Golden Twenties) of Germany proved to be endlessly influential to the modern outlook on queer art and cinema. It was no utopia, but the blind eye of authorities and the increase in gay acceptance resulted in an explosion of culture and art that the country had never seen before. If nothing else, it proved that queer art has always existed— even in spite of censorship— and has served as a powerful force that aided in the renaissance of a country, and provided solace in even the most unlikely of places.